The film maker was Andrew Kötting and the film was Gallivant, a unique work which has since been acclaimed as one of the best British films ever made and is now scheduled for a British Film Institute (BFI) 2k Blu-ray re-release this July.Released in 1996, Gallivant was Kötting’s first feature-length movie. It recorded a journey the director took clockwise around the coast of Britain accompanied by his 85-year-old grandmother, Gladys, and his seven-year-old daughter Eden, who has the rare genetic disorder, Joubert syndrome. The film, which starts in Bexhill and ends back in Hastings. is a sort of idiosyncratic British road movie. Gallivant premiered at the Edinburgh Film Festival, where it won the Channel 4 Best New Director prize. It was ranked number 49 in Time Out's list of the 100 best British films.

Writer Iain Sinclair, who has a home in St Leonards, in an early review of the film in Sight and Sound magazine, described it as: “A multiple-focus trek made within modest limits, cinema returned to its infancy. And without top-heavy production clutter or budgetary excess. This is a homage to that archetypal home movie, the seaside excursion. The day out, remission from mundane routine. Time for putting together oldest and youngest members of the family for that hell of British togetherness.”

Sinclair would later feature in a number of Andrew’s subsequent films, some of which have strong links to the Hastings area.Going back to the phone call - it was from Hastings Jack in the Green founder Keith Leech who was trying to round up a few bogies after a request from Kötting - ‘It’s ten minutes filming down by the net huts and he said he’ll get the beers in for us at the pub’.A handful of showed up in our green rags and ivy headdresses and cavorted and hollered in the autumn dark among the tall black net huts as Andrew filmed. There was no set, sound crew, cameras on rails or trolleys, and his only direction was just do want you want and go wild. This was film making gone native and primitive, boiled down to its essential elements with no waste and little, I imagine, to litter the cutting room floor.Andrew later re-located from Deptford in London, to St Leonard’s, where he still lives, and I am lucky to have got to know him well. A fulcrum for unpredictable madness, an overheating engine room of febrile creative energy and a wellspring of generosity of spirit and constantly evolving ideas. To spend time with him, no matter how brief, is to be catapulted into a different reality and way of seeing. He is a seer, a mad prophet. His personality infectious. If it wasn’t for his big heart he would fit right in with the description of Byron as ‘mad, bad and dangerous to know.’ Kötting is dangerous if you cling to certain staid ideas and are terrified of having the rug pulled out from under you.What led Andrew to start and finish his coastal odyssey in Bexhill and Hastings, were fond childhood memories of seaside family holidays. He recalls: “My Grandparents used to bring us to Bexhill-on-Sea for our summer holidays when I was very young. All five grandchildren, four boys and a girl. We would pitch tent inland at Little Common for the first few years before they invested in the hire of a caravan. Not posh but with an awning it slept six, we were very much on top of each other, winceyette sheets and nylon pillows with thick rashers of bacon for breakfast. My grandmother worked as the store’s mistress at a cottage hospital in Sidcup, we were never short on catering packs of foodstuffs.

“At least once a week we’d drive to the De La Warr Pavilion for beach side fun followed by hard scones, warm clogged cream and cold tea in the gloriously dilapidated architectural aberration. And all of this for a pound each. Gladys, my grandmother loved it, Albert my grandfather put up with it. By the time I was 16 I would come down with friends from school and we’d stay in the caravan and then in the evening cycle into Hastings for some action.”

Kötting imparts the gift of resonance. You may not get his films at first encounter, but they quickly embed themselves into peripheral memory - become an itch you can’t scratch - the pearl in the oyster. But that’s fine. How many of us have heard a music album which did not connect on the first spin, but on repeated listening became essential to our lives. Films are like that - they require re-visiting. You wouldn’t buy a CD, listen to it once then throw it in the bin.Gallivant is heart on sleeve and heart in mouth cinema. Life as it happens and unfolds in all its colour and uncertainty. He set some unstable contraption into motion then raced down the road to keep up with it, arms flailing, barely holding on and, notably falling off at one point. The film is a hair-raising ride, an adrenaline rush at times, while capturing the elusive melancholy light of the English landscape and calm islets of meaningful human interaction.It almost transcends the Kötting mantra of reverse engineering - creating the action first and finding narrative and meaning later - because people find their own meanings and interpretations of the work. It’s a sand box, an insane canvas on which to project ideas and feelings. Perhaps that is part of the reason it has survived and persisted - is still relevant today.The items on offer on Kötting’s market stall (he had one once) are the archetypes of landscape and human interaction. Gallivant is future proofed and will still be as relevant in the next quarter of a century and beyond.The siren song of Gallivant will continue to lure unwary sailors and dash their pre-conceptions on its rocks. I guarantee it will be a shipwreck to remember.

Gallivant is re-released on July 17 and the Blu-ray disc contains a number of Andrew’s earlier short films.

Have you read? In pictures: Bexhill holds medieval themed pageant

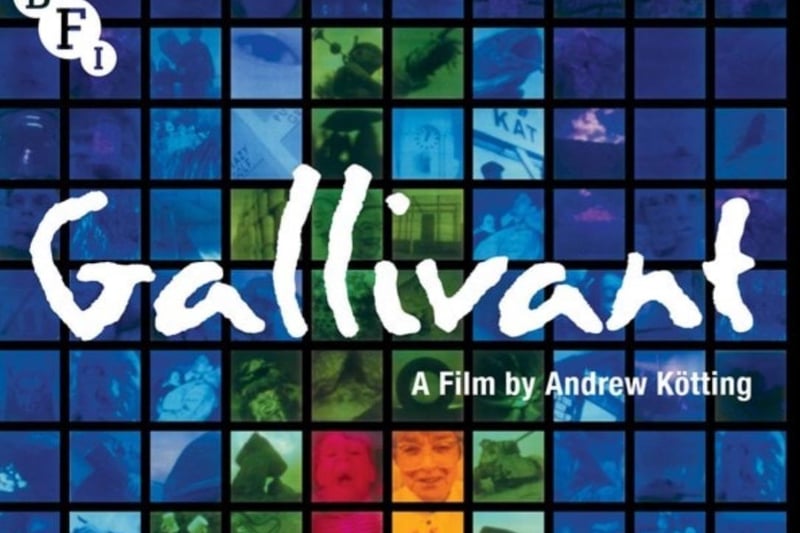

1. Gallivant

Gallivant is re-released on Blu-ray on July 17. Photo: supplied

2. Gallivant

Gladys and Eden at Bexhill Photo: supplied

3. Gallivant

Madcap genius Andrew Kötting. Photo: supplied

4. Gallivant

Andrew pictured at this year's Deptford Jack in the Green Photo: supplied