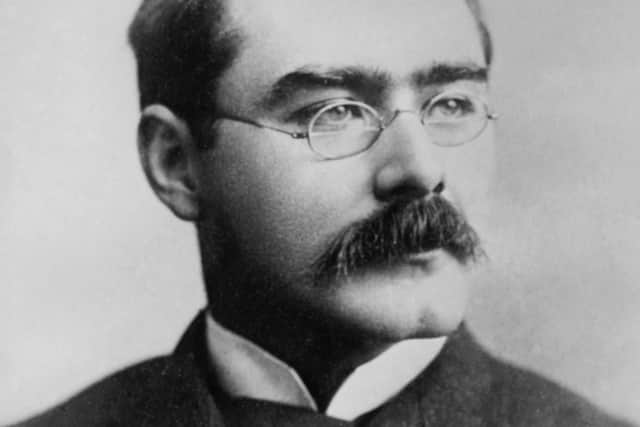

Rudyard Kipling's fine Sussex tale of ghostly consolation

Rottingdean's recent two-week Kipling Festival, celebrating the village's most famous former resident, involved a variety of events, including exhibitions, readings, talks, and tours.

The one I caught, at The Grange, was a fascinating group discussion of his short story 'They', a favourite of mine among Kipling's works. If you associate Kipling with India and militaristic or imperialistic themes, then I recommend this story, which could not be further removed.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Kiplings lived at The Elms from 1897 to 1902, and in many ways it was a very happy and productive period, surrounded by relatives, including the Burne-Joneses and Baldwins. An exhibition of about 50 family photographs taken at Rottingdean in 1898 gave an invaluable glimpse into this period of his life. He claimed he was driven from Rottingdean by the sightseers and autograph-hunters besieging his home, but I imagine the tragedy that befell his eldest child was also a factor. Josephine was just six when she died from pneumonia in 1899. Thereafter, he says, wherever he went in The Elms, he sensed her ghost following him about.

'They', written soon after the move to Bateman's at Burwash, is an attempt to allay the grief he still felt. The narrator, who is indistinguishable from Kipling, sets off by car from his home in the far east of the county. Kipling was a 'horseless carriage' pioneer, driving at this time a two-cylinder, 10 horsepower Lanchester with tiller steering. (He once ignominiously broke down on Brighton seafront 'under the eyes of 5,000 Brighton hackmen and about 2,000,000 trippers'.) I don't know how fast that thing went, or how long it would actually have taken to cover the distance described in the story's opening paragraphs, but the evocation of Edwardian Sussex is memorable.

'The orchid-studded flats of the east,' he says, 'gave way to the thyme, ilex, and grey grass of the Downs; these again to the rich cornland and fig-trees of the lower coast, where you carry the beat of the tide on your left hand for fifteen level miles.' From the Pevensey Level, perhaps, across to Rottingdean, then 15 miles along the coast through Brighton to Worthing, along a litoral as yet untouched by bungalow, villa or mall. Here he turns inland to Washington and 'hidden villages where bees, the only things awake, boomed in eighty-foot lindens' and a fox rolled 'dog-fashion in the naked sunlight'. He gets lost, finds himself descending, Alice-like, 'a gloomy tunnel', and comes out finally on a lawn among topiary knights and ladies. Beyond is an ancient house of 'mullioned windows and rose-red tile'. And at once he sees the first child, at an upper window, waving.

Over the course of the story, he will visit this mysterious domain three times, three times speak to the blind woman who owns it, three times glimpse, closer and closer, the fleeting children who haunt it. Children that only those who have themselves lost a child may see.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFinally, when he realises what they are, he decides he must come there no more. 'For you it would be wrong,' the blind woman agrees, though why wrong is left unspecified.

I think Kipling felt that, though spiritualist communication was tempting - his own sister was an ardent attender of seances - it was not the right thing for him. He evokes the realm of the children with tenderness, but knows he cannot stay there. He must return to his car - that symbol of material reality - and to his life on 'the other side of the county'. Which is to say to his writing, his vocation, his art.